Spielraumnetze *02

Big play spacenet at the Kinderparty 1971 in Berlin-Charlottenburg

In 1971, Conrad Roland wrote in his self-published brochure that his "play spacenets" were "a natural and crucial preliminary stage for a future socialist world of living, working, recreation and playing". 1 A lofty claim – but was it really an educational impulse that prompted the architect and engineer to no longer just deal with gigantic high-rise constructions and hanging cities, but to produce playground equipment? Or was it more a step out of necessity?

His ambitious designs for variable spatial cities with modular living units were far from reality, his dissertation faltered – and money was running out. Götz Aly, historian and Roland's brother-in-law, remembers a conversation over "Cigarette smoke and gin" 2 in the winter of 1969/70, in which he advised the disillusioned Rolandto realize his castles in the air on a scale for children first. Aly later referred to himself as a "midwife for the realization of the brilliant idea of a highly creative, not always easy, but lovable person". 3 Despite all the theoretical exaggeration of the climbing nets, the step into practice was probably more pragmatic than programmatically motivated.

In a retrospective, the Deutsche Bauzeitung described the birth of the spatial play nets as follows:

"If he did not want to let die the idea of using minimal nets not only to span factories and sports facilities, but to make them available to children as safe playground equipment, he had to take the construction of the first climbing frame into his own hands. And so, as a kind of by-product of Frei Otto’s Montreal and Olympic tents, Conrad Roland’s climbing frame production was born." 4

A Time that Wanted to Play

Whatever his motivation, Roland's bold climbing structures found fertile ground in the early 1970s. Cities were suffering from a shortage of building land and exploding property prices, and new large housing estates were springing up – often leaving only poorly designed leftover spaces for children. "The child's endangerment and lack of space are one of the most alarming aspects of the 'planned chaos' called architecture and urban planning," 5 he aptly said in an article in DIE WELT in March 1971. Roland observed this misery with a sharp eye and biting irony: "Fortunately, children cannot be forced to play," he wrote. "if they don't like a playground or playground equipment, they follow their own desire alone and look for something better." 6

What began as a simple climbing game evolved – through creative refinement and functional expansion – into a versatile spatial construct for the backyard and beyond. From climbing nets to pavilions, from baby play equipment to hanging bars for teenagers – openness of use was the guiding principle. Later, the catalogue referred to it as "super furniture" with a wink:

"Not only children, but above all parents and other serious people will discover unexpected pleasure in these new trembling, wobbling, and swinging nets, climbing around and shimmying for morning or evening exercise as well as sitting, lying, dozing and sleeping on and in the spacenet in different planes and positions." 7

These unconventional suggestions were more than marketing: they reflected a new zeitgeist. Roland's nets were an expression of a transforming society where play spaces were being reimagined politically, aesthetically, and educationally—closely linked to the changing understanding of pedagogy in those years: away from authoritarian parenting styles and towards an image of the child as an active, creative person. The aim was to create spaces in which children could act, create and explore their environment in a self-determined manner – free from rigid rules and with room for imagination. Roland's designs were an exemplary spatial implementation of these new educational ideals: a designed freedom that allowed children self-determination and creativity through play.

It was no coincidence that in 1971 with his “Riesen-Oktanetz” a piece of playground equipment received the special prize of the Federal Prize “Gute Form” (eng. "Good Form"): the child and its needs had clearly moved into the centre of social discourse. One goal of the prize, sponsored by the German Ministry for Economic Affairs, was to promote design as a holistic factor in international competition. Roland's net was thus not only a functional piece of play equipment, but also became an ambassador for a new understanding of play and urban space. It combined aesthetic quality with social standards and became a worldwide export hit.

From the Play Spacenet to the “Seilzirkus”

Initially, Roland’s focus was less on children’s emotional well-being and more on the joy of building, inventing, and experimenting. His first playground equipment was created in his studio in Berlin. There, the playground was his lab, and the child was not so much the object of pedagogical care as a participant in an architectural experiment.

In 1970, Roland began the first attempts to make spacial nets usable for children's playgrounds. These so-called "play spacenets" were stretched into external tubular frames. As part of the "Children's Party" at the Berlin Exhibition Centre in 1971, his prototypes were tested in public for the first time, accompanied by great media interest. At the same time, Roland self-published the booklet "Spiel-Raumnetz + Spielstadt" (eng. “play spacenets + play city”) with designs and ideas for further development. At the same time, he was still working on his dissertation on hanging houses – until he finally broke it off in mid-1972 to devote himself entirely to series production. The Berlin Rope Factory initially produced his play structures under license. In 1972/73, Roland applied for numerous patents in eight countries, including for mast feet and cable tension systems.

A year later, a new generation of playground equipment followed with the "Seilzirkus": instead of outer frame constructions, Roland now relied on inner mast tubes. The large three-masted "Seilzirkus" was shown at the International Garden Exhibition (IGA) in Hamburg in 1973. In 1974, Roland founded his own company Spielbau Conrad Roland, which was renamed Corocord Spielbau GmbH the following year. At the IGA Mannheim, he presented the “Super-Zweimast-Seilzirkus“ (eng. “the super two-mast rope circus”), the world's largest play structure at the time. This was followed by international commissions – including in Abu Dhabi, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia – numerous new developments with rubber membranes and accessories, and a solo exhibition in Hamburg. Sales had by now expanded worldwide: Europe, the USA, Japan, Singapore, and Australia.

By 1980, Roland had developed a large number of spacenets and rope circuses in various sizes and configurations. In 1985, he sold his company to a consortium that continued production under the name Corocord Raumnetz GmbH. In 1987, he presented the world's largest spacenet to date at the Federal Garden Show in Düsseldorf – another milestone in his career. From 2006 to 2008, the company finally became the property of Kompan. The Corocord brand was finally discontinued in 2019. Today, only parts of the original product line remain available.

When Utopias Arrive in Everyday Life

In retrospect, Roland's fantastic visions of suspended cities remain utopian even at the playground level. The exuberant fantasy of a spacenet play city with a theatre hall and a play city council, with little colourful houses, a mirror hall high above the ground, a dark cave with underground tunnels, floating streets, a roller-coaster-like bike path, a post office, a cinema, and telephones everywhere on the net and above all a colourful roof that could be opened and closed, 8 remained a dream. But the underlying idea of a play world, "which the children can build themselves in a very large spatial net and transform, rebuild and rebuild again and again", 9 did become reality. Roland explicitly didn’t want this to be "a dream for rich people's children". 10 Today, his spatial and rope nets are part of everyday playground life and are accessible to everyone – worldwide and regardless of social status.

MG, 12.4.2025

1 Conrad Roland: Bauen mit Raumnetzen 1. Spiel-Raumnetz + Spielstadt. Kletter- und Spiel-Geräte aus räumlichen Seilnetz-Konstruktionen. Vom Bau-Spiel der Kinder im Spiel-Raumnetz zum Stadt-Bau-Spiel im Wohn-Raumnetz. Berlin 1971 [Self-published]

2 Götz Aly: Zum Tod des Architekten Conrad Roland. Berliner Zeitung, 13.10.2020.

3 Ibid.

4 Wie ein Ingenieur Spielgeräte-Hersteller wurde. Deutsche Bauzeitung 8/79, p. 45.

5 Anna Teut: Berliner Spielparadies für Kletterkinder. DIE WELT (76), 31.3.1971.

6 Roland (1971): Bauen mit Raumnetzen 1, p. 4.

7 Ibid., p. 25.

8 Cf. ibid., p. 31.

In 1971, Conrad Roland published his first catalogue as a self-published booklet: a copied and stapled brochure containing sketches, construction plans, and reflections on the idea of play as an active, physical, and creative experience of space. The catalogue covered a broad thematic range – from general considerations about urban play spaces, to climbing techniques, net types, and construction principles, all the way to safety aspects, model variations, and modular extensions.

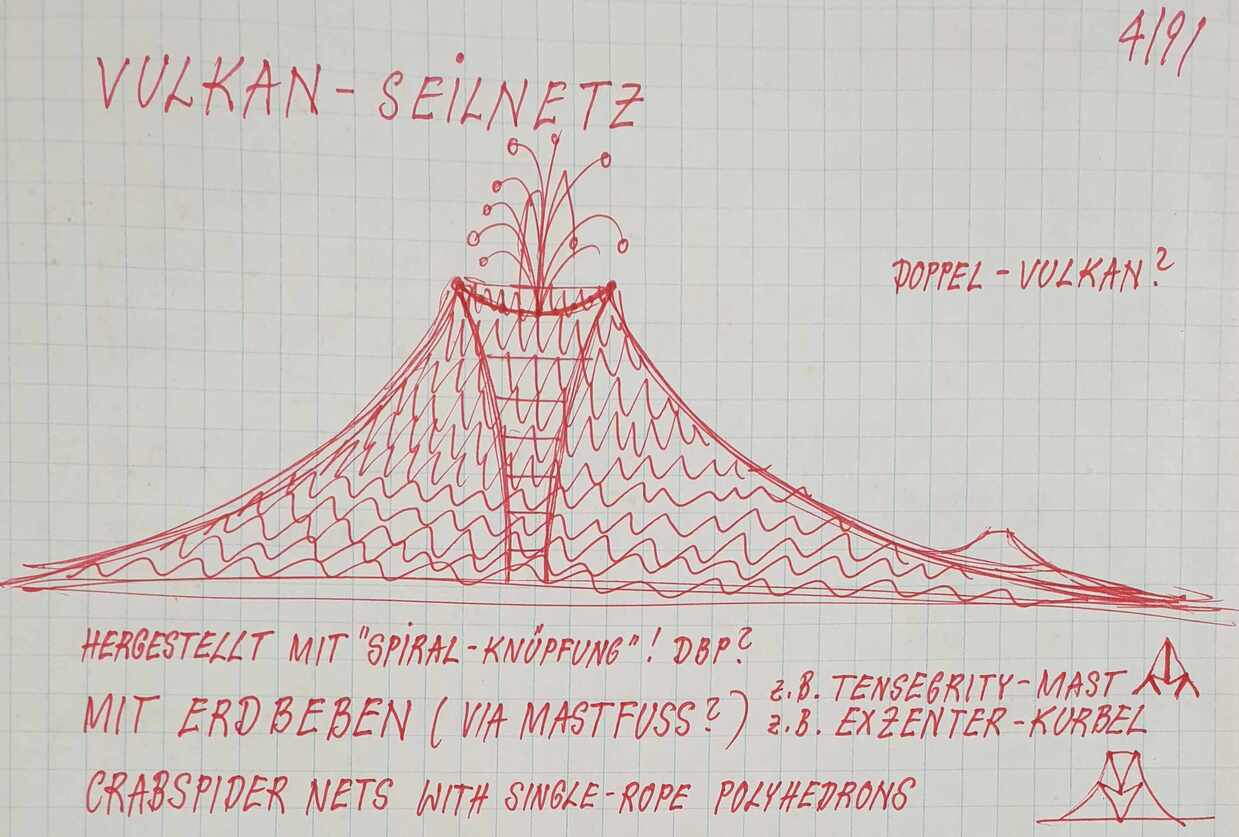

Even after the sale of his company in 1985, Roland continued to work on the development of his space and cable nets. As a tireless tinkerer, he tested new materials, improved tensioning systems, and developed modular extensions. In addition, there was an increasingly sophisticated playful dramaturgy: the net was no longer understood only as a climbing structure, but as a designable experience space – as here in the shape of a volcano.